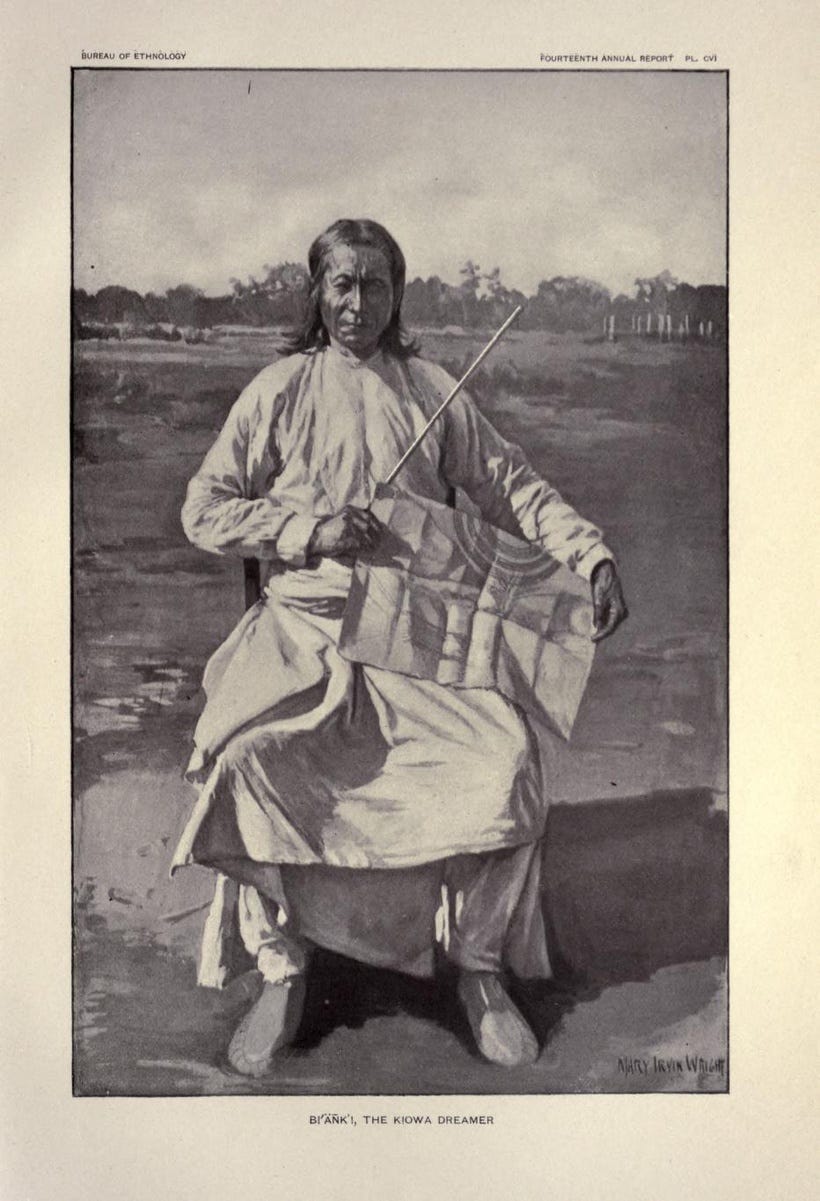

In the late 19th century, the Ghost Dance cultural-religious revitalization movement reached the Kiowa people of Oklahoma. This gave rise to a number of local prophets and visionaries. Among them was a man named Bi’anki. He was described by the ethnologist James Mooney as an intellectual, “quiet and dignified in manner, with a thoughtful cast of countenance which accords well with his character as a priest and seer.”

Through fasting and prayer, he undertook “frequent visits to the spirit world” in order to obtain knowledge and information for his people. These were done for the benefit of the community, to discover new remedies for illnesses and to deliver messages from souls of the dead to their living relatives. As a result of these experiences, Bi'anki became known as Asa’tito’la, “The Messenger.” I’ve come to think of these kinds of experiences “shamanic NDEs” because the individual deliberately pushes the body to physical and emotional extremes until they enter a death-like trance state. The explicit intention is sending the soul to the otherworld then returning to the body.

In 1896, Mooney published a detailed narrative of one of Bi’anki’s particularly vivid shamanic near-death experiences. Unique among Native American NDEs, and incredibly rare in accounts around the world, Bi’anki actually illustrated his experience. Preserved and published by Mooney, the account is given in full below — together with Bi’anki’s original illustrations.

After reaching the spirit world he found himself on a vast prairie covered with herds of buffalo and ponies, represented respectively in the picture by short black and green lines at the top. He went on through the buffalo, the way being indicated by the dotted green lines, until he came to a large Kiowa camp, in which, according to their old custom, nearly every tipi had its distinctive style of painting or ornamentation to show to what family it belonged, all these families being still represented in the tribe. He went on to the point indicated by the first heavy blue mark, where he met four young women, whom he knew as having died years before, returning on horseback with their saddle pouches filled with wild plums.

After some conversation he asked them about two brothers, his relatives, who had died some time ago. He went in the direction pointed out by the young women and soon met the two young men coming into camp with a load of fresh buffalo meat hung at their saddles. Their names were Emanki’na, "Can’t-hold-it,” a policeman; and E’pea, “Afraid-of-him,” who had died while held as a prisoner of war in Florida about fifteen years before. It will be noted that they are represented in the picture as armed only with bows and arrows, in agreement with the Ghost Dance doctrine of a return to aboriginal things.

After proceeding some distance, Bi’anki retraced his steps and met two curious beings, represented in the picture by green figures with crosses instead of heads. These told him to go on, and on doing so he came to an immense circle of Kiowa dancing the Ghost Dance around a cedar tree, indicated by the black circle with a green figure resembling a tree in the center. He stood for a while near the tree, shown by another blue mark, when be saw a woman, whom he knew, leave the dance. He hurried after her until she reached her own tipi and went into it — shown by the blue mark beside the red tipi with red flags on the ends of the tipi poles — when he turned around and came back. She belonged to the family of the great chief Sett'ainti, “White Bear,” as indicated by the red tipi with red flags, no other warrior in the tribe having such a tipi.

On inquiring for his own relatives Bi’anki was directed to the other side of the camp, where he met a man — represented by the heavy black mark — who told him his own people were inside of the next tipi. On entering he found the whole family, consisting of his father, two brothers, two sisters, and several children, feasting on fresh buffalo beef from a kettle hung over the fire. They welcomed him and offered him some of the meat, which for some reason he was afraid to taste. To convince him that it was good they held it up for him to smell, when he awoke and found himself lying alone upon the mountain.

Mooney also published a drawing of Bi’anki, traced from the original photo at the top of this post (which I found in the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution).

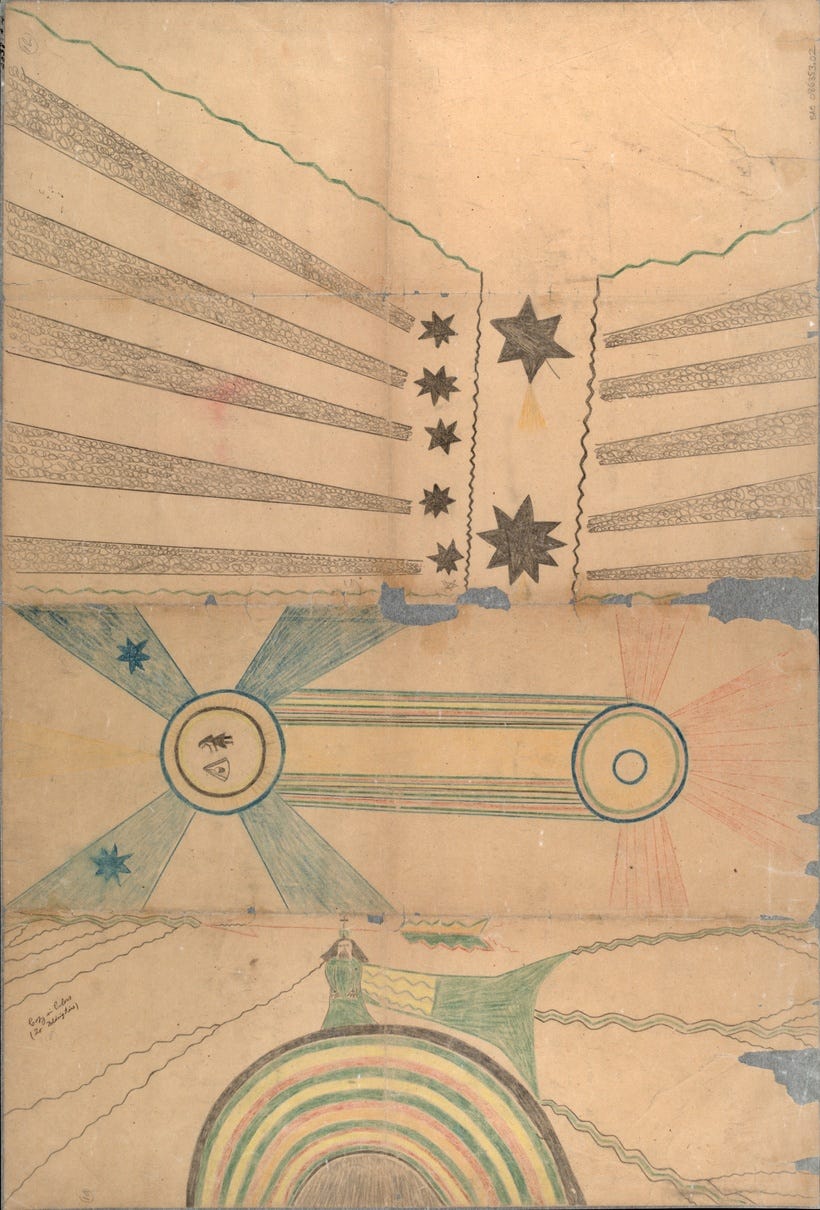

In the photo, Bi’anki “holds in one hand a paper on which is depicted one of his visions, while in the other is the pointer with which he explains its meaning.” I also found in the Smithsonian archives the actual drawing that Bi’anki is holding in the picture, labelled “Bianki drawing of his vision to the spirit world.”

This image was previously unpublished — until it was used for the cover of my award-winning book Near-Death Experience in Indigenous Religions (just out in paperback!). With some speculative imagination, perhaps we can see such common NDE themes as radiant light, darkness, paths, tunnel, spirit beings, and a deity. It was drawn originally on separate sheets, which presumably indicate different stages of the experience.

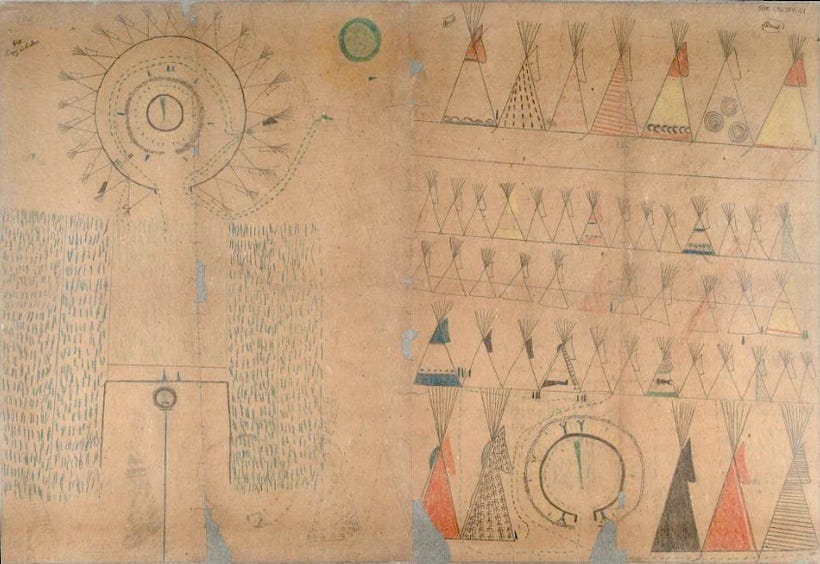

I also found two additional drawings by Bi’anki of his shamanic visions, never before published and not mentioned by Mooney. Unfortunately, as with the above, any additional descriptive information is lacking, and it’s not clear if all four drawings depict the same experience or more than one. But they’re fascinating to see — particularly the way they incorporate both indigenous and Christian imagery:

You can read more about historical Native American NDEs in comparison with those from Africa and Pacific in Near-Death Experience in Indigenous Religions.

From Rosetau to Xibalba with Gregory Shushan is free today. But if you enjoyed this post, you can tell Gregory that his research and writing are valuable by becoming a Patron. Depending on the tier you select, you will receive a copy of one of his books — or all three: Near-Death Experience in Indigenous Religions, The Next World: Extraordinary Experiences of the Afterlife, and The Crossover Experience (an introductory book on NDEs Gregory contributed to). You will not only be supporting his research and receiving a book (or books!), you’ll also get the Historical NDE of the Month direct to your inbox, exclusive content, news and updates, and a special thanks in his forthcoming books The Historical Anthology of Near-Death Experiences and To Die and Rise Again: Near-Death Experience in Classical Antiquity.

You can also make a one-off contribution via his website, or pledge a future subscription here at Substack. You won't be charged unless he enables payments.

Fascinating account. I was struck by the drawing that he was holding in his hand. It is beautiful and resembles the visionary art of Hilma af Klint.