Near-Death Experiences and the Origins of the Afterlife

Death is one of the few unambiguous facts of life. Together with birth, nothing could be more basic and fundamental to the universally human path of our existence. Our knowledge of the inevitability of death helps define life, and even to give it meaning.

As life’s opposing state, death makes us aware of the finite nature of our time on earth. This helps motivate us to act on our aspirations, providing a sense of urgency to achieve, to accomplish, to create and procreate, to strive for fulfillment and contentedness in the brief time we’re here — because on some level we continually carry with us the awareness that we won’t always be. Though we may feel on an existential level that it is ultimately fruitless, we are preoccupied with leaving something of ourselves behind, some evidence that we existed — a gesture towards some kind of legacy that will act at least as an emblem of immortality: children who look like us and think like us, or the material products of our creativity which we consider to stand for who we are — a book, a poem, a painting, a photograph, a favorite recipe — anything that attests to that fact that our individuality, our selves, were here and had some kind of impact and even purpose.

While most of us don’t often witness the violent destruction or physical decomposition of human bodies, we all experience the deaths of our loved ones. Their vision, their hearing, their engagement with the world slipping away, vital signs ebbing, color draining, and breath dwindling until that certain final whispery exhalation signals the end. The simple profundity of experiencing of another’s death, of witnessing their transition from alive to not alive, can’t be overstated. A human being once animated and dynamic, once so full of intention, action, and thought, never to move, think, speak or smile ever again, never to interact with us again for the rest of our lives on Earth. The evidence of our senses confirms to us that every living thing will die, including our families, our friends, our pets, and ourselves.

And yet, the sense that our bodies are not entirely “us,” that they are really just the things that carry us around, the machines that house our ghosts, is embedded in our very languages. We spend our lives alternately identifying ourselves with our bodies, and distancing ourselves from them. We say “I am hungry” instead of “my body is hungry,” and “I am dying” rather than “my body is dying.” But we also refer to our minds as being distinct from our bodies. We make up our minds, we change our minds, and we lose our minds.

Many of us — including atheists and agnostics — have vague, half-realized, or even totally subconscious feelings that when deprived of our bodies we must still be something. If this body is not quite entirely “me,” I am more than just my body, and something other than death must happen to “me” when my body dies. And of course, most of the 98% of the world’s religious people firmly believe that they’ll survive their own deaths, whether in some heavenly or hellish realm, through resurrection, reincarnation, or even liberation from the cycle of births and deaths.

Experiments in cognitive neuroscience seem to show that we’re hard-wired to believe in an afterlife, despite the evidence of death all around us. Very young children who have little conception of the metaphysical implications of death or afterlife seem to intuitively believe that physical death somehow does not entail the death of the “person.” They naturally assume that it isn’t really the end, and that “dead” people live on somehow, somewhere. At least since Freud, it’s been said repeatedly that we’re simply unable to imagine our own nonexistence. We haven’t had the experience of being dead, and it’s impossible to know what it’s like to be wholly without perception, sensation, awareness, and thought.

Psychologists, philosophers, anthropologists, and sociologists of all description have weighed in with attempts to explain afterlife beliefs without reference to the theological or metaphysical. They hypothesize that they’re due to either wish-fulfillment fantasy, to a yearning for justice in compensation for earthly unfairness, to observations of the “dying-and-rising” cycles of nature, or to the priests and kings who control the world through threats and promises of post-mortem punishment and reward.

These are all interesting theories as far as they go, and each has a place in explaining certain characteristics of specific beliefs in particular societies. But they all ignore two very important things.

The first is the existence of afterlife beliefs around the world that don’t fit into such neat categories. Although virtually every society in nearly all times and places has some kind of belief in consciousness surviving bodily death, the conceptions are different enough that such generalizations are unfounded. For example, not all societies believe in moral judgement in the other world, meaning that their beliefs were unlikely to have been created by the elite as a tool of social control.

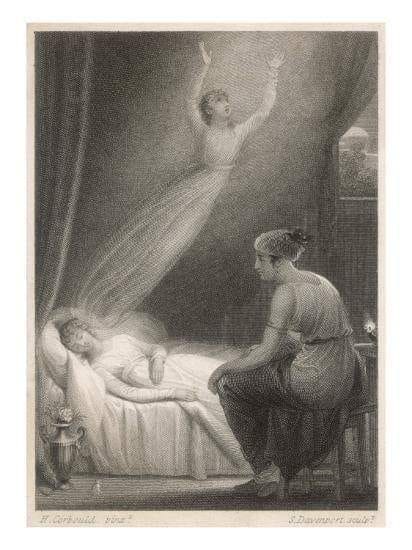

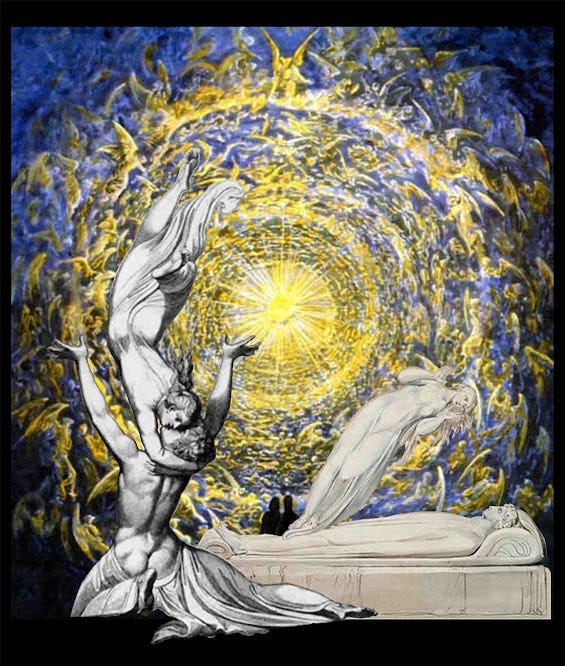

The second thing all these theories inexplicably ignore is the single human experience that is actually the most relevant to beliefs in an afterlife: near-death experiences, or NDEs. Though often misunderstood to mean simply a brush with death, NDEs are far more complex and far more interesting. The term actually refers to people whose brush with death left them unconscious or even temporarily dead from a clinical standpoint, and upon revival they tell of the spiritual experiences they underwent. Typical elements to those experiences include leaving the body, entering and emerging from darkness, bright light, visiting another realm sometimes seen as the true home, meeting deceased relatives, encountering a being of light that some associate with a particular religious figure, a moral evaluation of one’s earthly life, and feelings of joy, peace, oneness, transcendence, or unity. NDErs then reach some kind of barrier or limit and are told (or decide) to return the body. Sometimes they are reluctant to do so, and are horrified at having to go back inside that cold, dead, horrifying thing lying there.

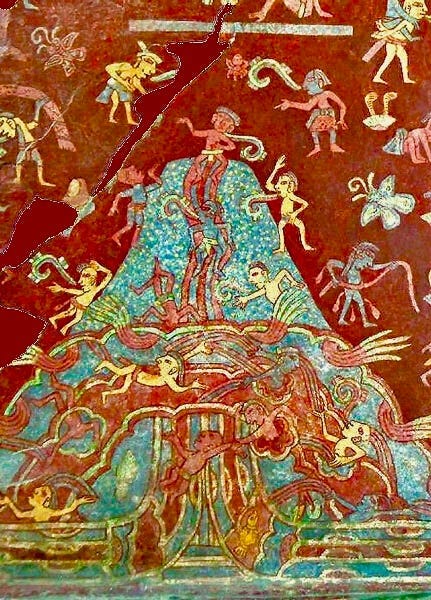

NDEs were only popularly recognized in the mid-1970s, but people from the largest empires to the smallest hunter-gatherer societies have been having them throughout history. Accounts are found in ancient sacred texts, historical documents, anthropological studies, and journals of explorers and missionaries. Among the dozens I’ve collected are those of a 7th century BCE Chinese provincial ruler, a 4th century BCE Greek soldier, a 15th century Mexica princess, two 16th century Algonquin Native Americans, two 18th century British admirals, a 19th century Ghanan victim of human sacrifice, a number of early 20th century Kiwai Papua New Guineans, a mid-20th century Samoyed Siberian, and a Soviet man who was revived from a suicide attempt through government resuscitation experiments. NDEs can happen to followers of any religion, and to those of none.

Just as the evidence of our senses tells us that everything dies, NDErs seem to have another kind of evidence, inaccessible to the rest of us, leading them to the opposite conclusion: that we do not die. In both the historical and modern accounts, NDEs often lead directly to new beliefs, including that consciousness can separate from the body, and that it can continue after death. In my book Near-Death Experience in Indigenous Religions I unearthed more than 70 Native American NDE accounts from the 16th-19th centuries, and over 20 of them were considered to be the direct source of “knowledge” about the afterlife. On the microcosmic level, the religious, agnostic, and committed atheist alike typically change their beliefs and worldviews following NDEs. Perhaps most famously, upon revival from his NDE, atheist philosopher A.J. Ayer told his doctor, “I saw a Divine Being. I’m afraid I’m going to have to revise all my various books and opinions.”

Scientists and philosophers generally accept that NDEs occur, though most reject the idea that they’re evidence of an afterlife. Instead, the experience is explained away as the hallucinatory special effects of a compromised brain. But some have reached the opposite conclusion. They point to reports of children meeting deceased relatives they never knew they had; of encounters with a person not known to have died; of the congenitally blind seeing for the first time during the experience; of temporarily brain-dead patients accurately describing surgical procedures they witnessed while out of their bodies; and of the seemingly miraculous positive transformations individuals so often exhibit following NDEs. According to his wife, A.J. Ayer “became so much nicer since he died.”

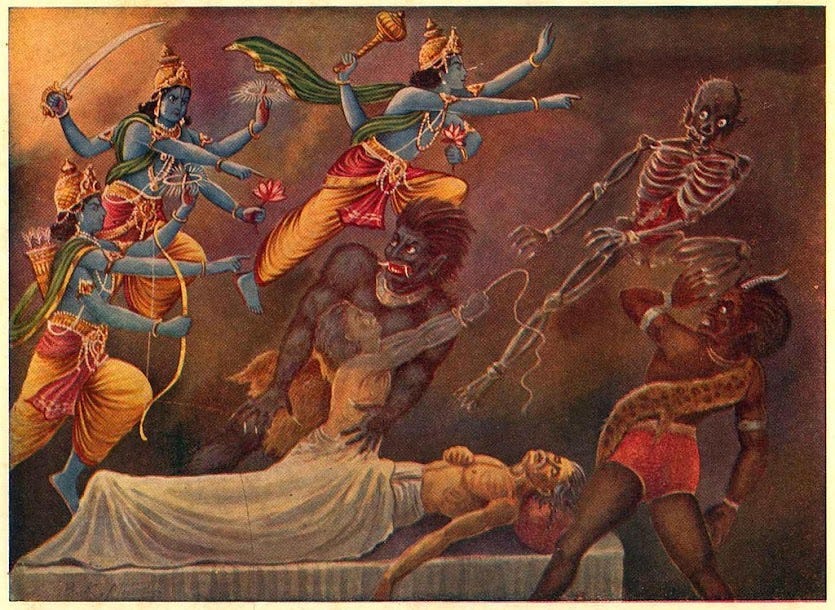

Whatever their source (biological, psychological, or metaphysical), there’s no question that NDEs are part of human experience. And while they share similar themes wherever they occur, no two descriptions are exactly alike. As with any other experience, NDEs are filtered through our layers of culture, language, and individuality. One person reports meeting Jesus in the form of a centaur riding a chariot, another encounters a Hopi sky-god, and another a transcendent identity-less being that radiates light, love, and acceptance. Descriptions of afterlife realms and other details of the experience also vary widely, according to culture and individual. Nevertheless, the experience is virtually always understood as “this is what happens when we die.”

Historically speaking, NDEs have played a major role in our beliefs about souls, bodies, and death. Typical NDE features such as the life review and beings of light are also worth thinking about in terms of our ethical systems, and beliefs in gods and spirits. Indeed, NDEs and other extraordinary experiences may have laid the very foundations of religions per se.

As a historian of comparative religions and related experiences, I’ve stayed mostly on the sidelines of the debate about whether or not these experiences are evidence for an afterlife (incurring suspicion and occasionally wrath from both camps). My main interest is in understanding why religious beliefs and experiences are similar across cultures, and why they’re different. The true nature of NDEs is separate from the idea that they can inspire, influence, and even give rise to afterlife beliefs. But as I’ve discovered in nearly every talk, interview, or casual discussion I’ve had about my work, when it comes to NDEs the question “but are they real?” eclipses all others. So profound is our desire to know what happens when we die that despite nearly 50 years of near-death studies, the cultural and religious aspects of NDEs have gone largely unexplored, trampled beneath the rush to debate their value or otherwise as evidence of an afterlife.

Of course, it would also be monumental if NDEs were to conclusively prove survival after death — that they really are a glimpse into another world and a taste of the true spiritual reality. Many researchers believe the existing evidence is already enough to prove it, while ongoing hospital experiments are seeking replicable evidence under controlled circumstances. Researchers place objects up near the ceiling in hopes that a patient will see them while outside the body, and accurately describe them. It’s no exaggeration to say that the success of such an experiment — proving both mind-body dualism and the survival of consciousness after physical death — would probably be the most significant intellectual and spiritual development in all of human history. But until then, it’s important to recognize the other important thing about NDEs: they help us to understand how our very beliefs, and thus our very cultures, are formed, how they can change, and how we can change and become better human beings.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider becoming a Patron. Starting at just $1 a month, all Patrons receive a Historical Near-Death Experience of the Month, sent to all my subscribers twelve times a year. Depending on your subscription level, Patrons also receive books, discounts, exclusive content, updates on my various activities (articles, interviews, exclusive content, and books published by my new Afterworlds Press imprint), and more. If you’d like to sign up or learn more about the benefits available, please click here.

For more about me and my work, visit my website www.gregoryshushan.com. And check out my new book from White Crow, The Next World: Extraordinary Experiences of the Afterlife.