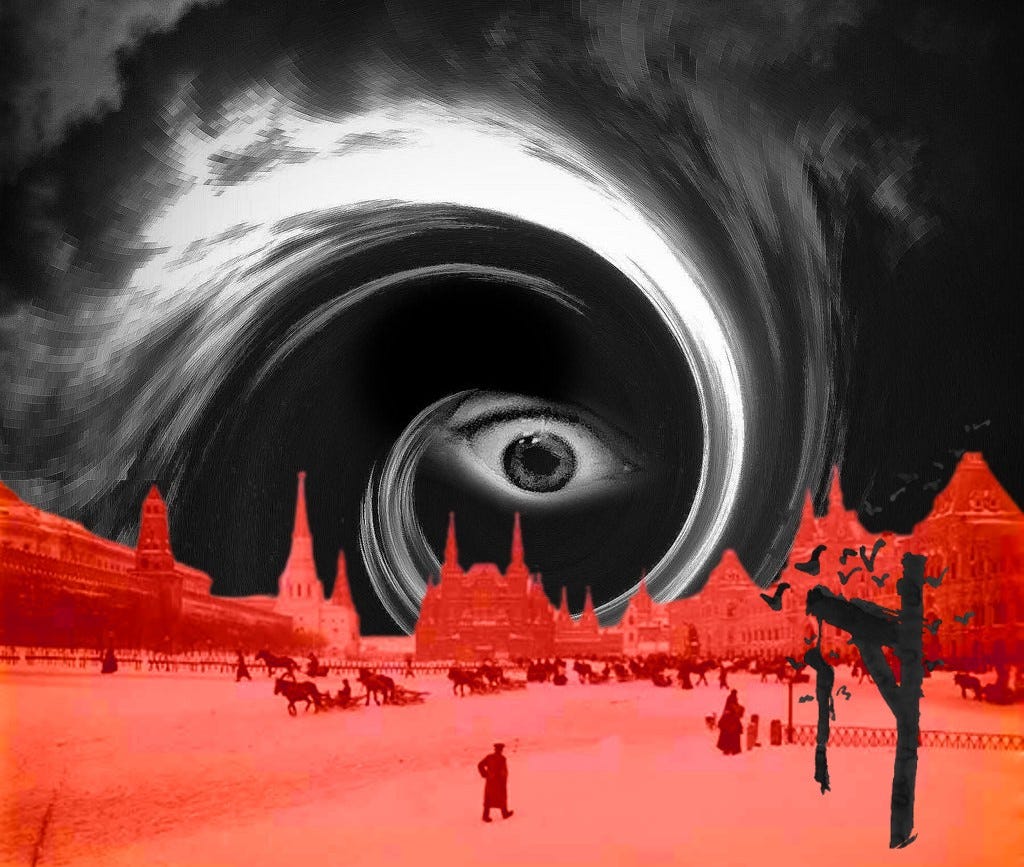

The Suicide of Red Square (Historical Near-Death Experience of the Month)

And a Halloween Meditation on Fear

With the approach of Dias de los Muertos, Halloween, Samhain, and All Soul's Day, I find myself thinking about the nature of fear, and especially how it differs between individuals and cultures. For many, the unknown — particularly the "paranormal" or "supernatural" — are the main sources of fear. This is perhaps especially so for those who believe in heaven and hell.

While the prospect of suffering, of leaving our loved ones behind, dying before we've fulfilled our dreams, or simply not existing might be terrifying, what lies beyond physical death is "just" a mystery. Fear of death because of that seems odd. A good and well-known definition of anxiety is intolerance of uncertainty, and as the ultimate, final, and most literally existential question, death is the biggest uncertainty of all. This means that even if we remove the "supernatural" from death, it remains a source of fear.

While death and the afterlife are indeed unknowns for all of us, near-death experiences often mitigate the fear of death. This applies whether we've had one ourselves, or simply through our knowledge of them. NDErs may feel (or, from their perspective, know) that they've been blessed with the transcendence of that mystery, and perhaps they have. But even if their experiences were genuinely glimpses of an afterlife, they only tell us what it was like for a particular person during a particular experience. What awaits them at the moment of their "actual" death, and what awaits us as individuals, is still unknown. This is suggested by the very different NDEs found across cultures and throughout history.

Personally, I have no fear of the "paranormal" or "supernatural." This is partly because I don't believe in them. I mean this in two senses. For one, I have no firsthand, direct, objective knowledge that such things be (as Ambrose Bierce might have put it). I don't have a personal, compelling reason to believe them. At the same time, nor do I disbelieve them. The apparent evidence is too abundant and compelling to ignore. Not having been raised religious, perhaps it's just that I don't understand belief. There are only things I know and many, many more things I don't know. I'm therefore comfortable dwelling in the Cloud of Unknowing until such a time as I will know — whether that's somehow before my death or after.

The second sense in which I don't believe in the "paranormal" or "supernatural" is that if these kinds of events actually do occur, that would only mean only that we need to revise our definitions of "normal" and "natural." I take "paranormal" and "supernatural" to mean "not currently understood by science." When William James was writing research articles for the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research in 19th century, topics included hypnosis and phantom limb syndrome. This shows us that yesterday's parapsychology is often today's mainstream science.

Aside from that, likely influenced by many years of researching such subjects, the idea of various forms of communications or manifestations of souls of the dead holds no fear for me. If souls survive bodily death, they're just people without bodies. The cross-culturally common idea that death and the afterlife bring wisdom and spiritual enlightenment makes our forebears even less scary (though there are, of course, also plenty of cross-cultural beliefs in ghosts, hauntings, possessions, and so on). In fact, given the human propensity for cruelty and violence, I find souls of the dead to be far less of a threat than people who still have physical bodies.

Our deep, subconscious fears are as much a unique part of who we are as our sense of humor, our taste in music, or our capacity for empathy.

If I'm not afraid of the afterlife or ghosts, I wonder what am I afraid of? Obviously, environmental collapse, the specter of a third world war, and this chaotic age of angry, willful, divisive ignorance are all excellent fodder to feed our fears and anxieties. But even those are circumstantial fears. They're earthly fears, as opposed to the deep, subconscious fears that are as much a unique part of who we are as our sense of humor, our taste in music, or our capacity for empathy.

When studying NDEs, I sometimes pause to think about how the circumstances of a person's death might have affected them. Because the spiritual adventures of disembodied souls is largely the raison d'être of near-death studies, the embodied part of the experience is rarely considered. Descriptions of the individual's "death" or near-death is provided as context for evaluating the veridicality or otherwise of the account. This is the case in medical research into the phenomenon, as well as in popular accounts throughout history, which seek to convince the reader that it really happened. The intention is to convey that the person really was dead in order to imply that NDE was really an experience of survival of bodily death.

All this means that the individual might become secondary to their own experience — particularly of the time between the inciting event leading to temporary physical death or near-death, and the out-of-body and otherworldly experiences. In part, this is also due to the fact that the glorious experience of the NDE largely erases the horror of other aspects of death for the NDEr. But I've realized that, in addition to the possible physical pain and suffering of dying and the prospect of loss, what I'm most afraid of is that in-between moment of pre-death horror.

Even more specifically, I have a visceral, nauseating terror of my conscious reality being compromised by whatever physical trauma is happening to my body. Losing my powers of conscious observation, of critical evaluation, self-awareness, and accurate perception of the reality of my situation and surroundings. Losing powers of intellect, lucidity, and self-control, as they are overpowered by confusion, internal chaos, and a nameless incomprehensible fear.

Drilling even deeper into what's lurks beneath those fears, I realize that their root is the threat that the physical scrambling of my cerebral processes will prevent me from dying consciously.

Two cinematic examples illustrate what I mean (both, incidentally, in films that I don't rate highly). In David Lynch's 1990 Wild at Heart, there's a harrowing scene in which Sherilyn Fenn is in the aftermath of a car accident. Her friends have been thrown from the car and are lying dead on the ground. With blood streaming from the side of her head and soaking her clothes, she wanders around the crash site in a confusional, delusional state — preoccupied with finding her purse: "My mother's gonna kill me. It's got all my cards in it, and it was in my pocket, and now my pocket's gone. Gotta help me find it," she rambles disjointedly. "My mother's gonna kill me. It was in my pocket...." She then feels "something sticky" in her hair and screams for her hairbrush, again terrified that her mother will find out that she lost her purse. A moment later, she collapses to the ground, blood bubbles from her mouth, and she dies.

I'm guessing that Lynch's point here was a commentary on society's preoccupation with materialism and appearance, to the extent that this poor woman's last anguished words were, absurdly, "Where's my hairbrush!?" Not only did she not die consciously or mindfully, she died with fear and obsession about an insignificant worldly anxiety about her appearance.

The second example is more gratuitous: the infamous brain-eating scene in Hannibal (2001), sequel to Silence of the Lambs. The scene has Ray Liotta sitting at a table in a drugged and semi-sensible state, with the cap of his skull removed and his bloody brain visible and glistening. Anthony Hopkins begins cutting off bits of the brain before frying them in a pan. Ray Liotta comments favorably on the smell and asks for a piece, and Hopkins obliges — feeding Ray Liotta bits of his own cooked brain. Though almost comical in its revolting excess, the image of Liotta not knowing his own condition — that his brain is exposed, that he's being slowly and sadistically killed, that there is no hope for him — is grotesquely chilling.

This brings us to the NDE in question — certainly the most gruesome and disturbing account I've read. It's found in a German book by Jean-Baptiste Delacour, the English title of which is Glimpses of the Beyond: The Extraordinary Experiences of People Who Have Crossed the Brink of Death and Returned. Published in Germany two years before Raymond Moody's Life After Life, and before his coining of the term "near-death experience," the book is a rare collection non-Anglophone NDE accounts, and therein lies its main significance to the field. Otherwise, it was a popular mass market paperback, and lacks any sort of scholarly discussion or analyses. Delacour did not even give his original sources, or provide dates for the accounts. The most we can say about the following, then, is that it dates to sometime before 1973.

According to Delacour, the case received much attention in Russian scientific journals, so if any Russian speakers can shed further light on this case, please do so in the comments.

It concerns an unnamed man who hanged himself in Red Square after being left by the woman he loved. The body was found early in the morning by one of Lenin's soldiers, and he immediately thought of a certain Professor Brunchanenko, who had been conducting resuscitation experiments on animals. This soldier had heard of the professor's recent success of bringing a dog back to life for six hours, and knowing that the professor was at that moment at work in his laboratory, he phoned him and offered the body of the hanged man. Our Soviet Dr. Frankenstein agreed that it would be a good idea, and the body was brought to him.

While most of our Historical NDEs of the Month focus on the spiritual experience, because it's Halloween, and because of the relevance to this post, the full gory details are included....

The artificial-heart machine was attached to a man unquestionably dead. The machine began to pump, pulsing blood into arteries that seemed already lax and defunct. Again and again spurts of blood were forced into the dead man's system, blood to which oxygen and some cardiac stimulants had been carefully added.

The pumping in and sucking out of the blood proceeded with absolute precision. Electrical controls regulated the pulse of the artificial heart with perfect accuracy. Great patience was in order-hours of waiting. But at last the goal toward which they were striving was reached. The artificial-heart machine brought the hanged man of Red Square back to a new existence. To be sure, this life renewed was a weak thing, hanging by a thread. After all, in hanging himself he had severely damaged his larynx and jammed his tongue down his throat. Moreover, many changes had taken place throughout his whole body, deteriorations that are signs of death for those at all skilled in such matters.

For instance, the muscles had completely lost their ability to contract. They showed no reaction when stimuli were applied with electrodes. This indicated that the man must have been swinging a long time from the grating. The dilation of the pupils that occurs when the death agony is finished had long since come and gone. The pupils had contracted to less than their usual diameter. The eyeballs themselves had become soft and shrunken.

The skin had a parchment feel. When hot sealing wax was dropped onto it to see if it would cause a blister, the effect was negligible. The livid spots typical of a corpse had yet to appear. But the body was very cold.

"No question about it, his temperature will have to be raised. When organic oxidation stops, naturally the body heat drops. It was very cold outdoors this morning, too. The body has a lower temperature reading than the thermometer outside."

All available means were now brought to bear: slowly heated oil baths, electric heating pads wrapped about the limbs. Meanwhile, the artificial heart pulsed on, sending richly oxygenated blood into the arteries.

"He just moved his lips! He wants to say something, or —"

At this moment they heard a long, groaning sigh issue from the mouth of the man who had hanged himself in Red Square. "We've got this far, anyway. Now we've got to keep cool and keep going-just as long as the machines keep functioning. We've got to make it!" The artificial-heart machine pumped on and on, pouring life into a dead man from whom the only response so far had been a single sigh.

The next day the resuscitative process had reached a point at which the man was able to speak in whispers. The brain had begun to function again.

"I was in a country where I'd never been before. It was very big there, and so beautiful. I'd like to go back there again. I can still taste the sweet water that I drank there. For there was a fountain there and I drank out of it. I saw flowers that were three times as big as ours. They smelled sweeter than the prettiest flowers we have here at the height of summer.

"I saw a lot of people a great distance away. When I started to run toward them, they moved away from me just as fast. There was a drummer standing under a giant tree that seemed to reach the sky. This drummer didn't run away from me. He just stood there beating on his drum until I was close to him. I don't know whether it was he, but someone spoke to me. Someone said to me that everything was all right now and that I could fly, too, if I wanted. How heavy my arms and legs are now. I don't think I'll ever be able to move them again, for in that other land where I was, everything was light as a feather. If only those people hadn't kept running away from me.

"The drummer grew as big as the tree. I couldn't see his face any more. And then I started to run through all the beautiful greenness and to call out loud for someone. Now I know it was my mother I was looking for. But she has been dead a long time. Anyway, I went looking for her and someone told me I'd find her soon. But it'll still take quite a while. It's always a long time before you find the one you're looking for.

"Then I fell asleep under the big tree that reached way up into the sky.

"Now I'm not sure whether life in that other land was just a dream. Or whether I'm having a bad dream now."

They put many questions to this man who had crossed death's threshold. He lived on for four days. Then suddenly even the artificial heart seemed no longer able to hold him in the land of the living.

"I long to get back to the green land!" he whispered before he died. These were the last words to come from the mouth of the man who hanged himself in Red Square.

A good deal has been written in scientific literature about "the suicide of Red Square." He is cited as an interesting case of the revival of a person apparently dead, with the stipulation that in hangings death is apparently delayed for some time unless there has been a drop of at least 2 meters, or about 6.5 feet, to ensure enough impact to break the cervical vertebrae. But the case is also described as a classic example of resuscitating, albeit briefly, a dead human being.

While the rather sensationalist narrative style of the account might make us skeptical, the NDE itself rings true. For one thing, it took place in a (nominally) atheistic country where claims of an afterlife would be unusual, and awareness of the phenomenon of NDEs even more so. The description of the experience echoes many others across history, combining familiar elements with individual and cultural idiosyncratic elements.

In any case, the detailed description of the physical state of the man's body is horrific, even if it is intended to alert us to just how "dead" he was, and therefore how exceptional his revival and NDE were. But stressing the degree to which his body really was a corpse before resuscitation makes me wonder what it must have been like for the man to wake up in a corpse.

Many NDErs express revulsion at the prospect of returning to their bodies, but this case stands out. The man was revived not out of compassion, or hippocratic ethics, or any life-saving motive, but merely as a medical experiment occurring in the context of an oppressive society which did not afford him individual rights or freedoms. He was also brought back against his will after choosing to take his own life, and finding happiness in the otherworld. Worst of all as far as our theme here is concerned, given the degree to which his body had been compromised, his faculties could not have been fully functional. This is shown by the confusion he expressed about not knowing whether this grim Soviet laboratory was a nightmare or reality, or if the land he had just come from was his true home or just a dream. He likely had no understanding of his own damaged body or that he could not live much longer, and indeed his definition of "living" had itself become a source of confusion. He surely also suffered physical pain, and the emotional misery of having left that otherworld behind and not knowing what would come next.... His last days of being half-alive must have been a nightmare of overwhelming confusion, misery, and fear.

This Substack is free, though I’m allowing paid subscriptions for those who wish to support my work. Alternatively, become a patron on Patreon. All subscribers and patrons at any tier will receive one or more of my books and various other benefits.